What is Kawasaki Disease?

Blue indicates link

Kawasaki disease causes swelling (inflammation) in the walls of medium-sized arteries throughout the body. It primarily affects children. The inflammation tends to affect the coronary arteries, which supply blood to the heart muscle.

Kawasaki disease is sometimes called mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome because it also affects glands that swell during an infection (lymph nodes), skin, and the mucous membranes inside the mouth, nose, and throat.

Signs of Kawasaki disease, such as a high fever and peeling skin, can be frightening. The good news is that Kawasaki disease is usually treatable, and most children recover from Kawasaki disease without serious problems.

Kawasaki disease is a syndrome of unknown cause that results in a fever and mainly affects children under 5 years of age. It is a form of vasculitis, where blood vessels become inflamed throughout the body. The fever typically lasts for more than five days and is not affected by usual medications. Other common symptoms include large lymph nodes in the neck, a rash in the genital area, and red eyes, lips, palms, or soles of the feet. Within three weeks of the onset, the skin from the hands and feet may peel, after which recovery typically occurs. In some children, coronary artery aneurysms form in the heart.

While the cause is unknown, it may be due to an infection triggering an autoimmune response in those who are genetically predisposed. It does not spread between people. Diagnosis is usually based on a person’s signs and symptoms. Other tests such as an ultrasound of the heart and blood tests may support the diagnosis. Other conditions that may present similarly include scarlet fever, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19.

Symptoms:

Kawasaki disease signs and symptoms usually appear in three phases.

1st phase

Signs and symptoms of the first phase may include:

- A fever that is often higher than 102.2 F (39 C) and lasts more than three days

- Extremely red eyes without a thick discharge

- A rash on the main part of the body and in the genital area

- Red, dry, cracked lips and an extremely red, swollen tongue

- Swollen, red skin on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet

- Swollen lymph nodes in the neck and perhaps elsewhere

- Irritability

2nd phase

In the second phase of the disease, your child may develop:

- Peeling of the skin on the hands and feet, especially the tips of the fingers and toes, often in large sheets

- Joint pain

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Abdominal pain

3rd phase

In the third phase of the disease, signs, and symptoms slowly go away unless complications develop. It may be as long as eight weeks before energy levels seem normal again.

When to see a doctor

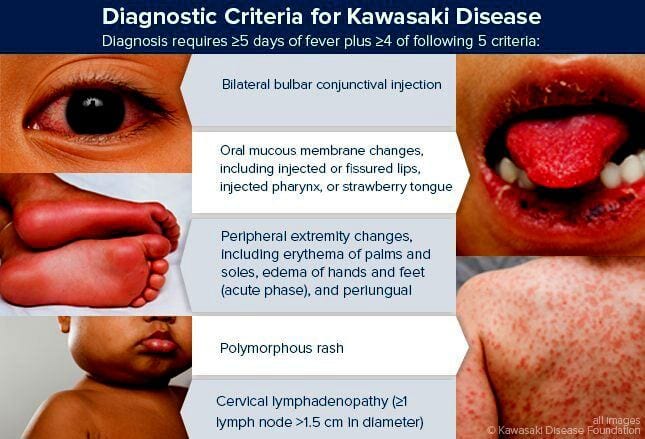

If your child has a fever that lasts more than three days, contact your child’s doctor. Also, see your child’s doctor if your child has a fever along with four or more of the following signs and symptoms:

- Redness in both eyes

- A very red, swollen tongue

- Redness of the palms or soles

- Skin peeling

- A rash

- Swollen lymph nodes

Treating Kawasaki disease within 10 days of when it began may greatly reduce the chances of lasting damage.

Causes:

No one knows what causes Kawasaki disease, but scientists don’t believe the disease is contagious from person to person. A number of theories link the disease to bacteria, viruses, or other environmental factors, but none has been proven. Certain genes may make your child more likely to get Kawasaki disease.

Risk factors:

Three things are known to increase your child’s risk of developing Kawasaki disease.

- Age. Children under 5 years old are most at risk of Kawasaki disease.

- Sex. Boys are slightly more likely than girls to develop Kawasaki disease.

- Ethnicity. Children of Asian or Pacific Island descent, such as Japanese or Korean, have higher rates of Kawasaki disease.

Complications:

Kawasaki disease is a leading cause of acquired heart disease in children. However, with effective treatment, only a few children have lasting damage.

Heart complications include:

- Inflammation of blood vessels, usually the coronary arteries, that supply blood to the heart

- Inflammation of the heart muscle

- Heart valve problems

Any of these complications can damage your child’s heart. Inflammation of the coronary arteries can lead to weakening and bulging of the artery wall (aneurysm). Aneurysms increase the risk of blood clots, which could lead to a heart attack or cause life-threatening internal bleeding.

For a very small percentage of children who develop coronary artery problems, Kawasaki disease can cause death, even with treatment.

Diagnosis:

There’s no specific test available to diagnose Kawasaki disease. Diagnosis involves ruling out other diseases that cause similar signs and symptoms, including:

- Scarlet fever, which is caused by streptococcal bacteria and results in fever, rash, chills, and sore throat

- Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a disorder of the mucous membranes

- Toxic shock syndrome

- Measles

- Certain tick-borne illnesses, such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever

The doctor will do a physical examination and order blood and urine tests to help in the diagnosis. Tests may include:

- Blood tests. Blood tests help rule out other diseases and check your child’s blood cell count. A high white blood cell count and the presence of anemia and inflammation are signs of Kawasaki disease. Testing for a substance called B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) that’s released when the heart is under stress may be helpful in diagnosing Kawasaki disease. However, more research is needed to confirm this finding.

- Electrocardiogram. Electrodes are attached to the skin to measure the electrical impulses of your child’s heartbeat. Kawasaki disease can cause heart rhythm problems.

- Echocardiogram. This test uses ultrasound images to show how well the heart is working and can help identify problems with the coronary arteries.

Treatment

To reduce the risk of complications, your child’s doctor will want to begin treatment for Kawasaki disease as soon as possible, preferably while your child still has a fever. The goals of initial treatment are to lower fever and inflammation and prevent heart damage.

Treatment for Kawasaki disease may include:

- Gamma globulin. Infusion of an immune protein (gamma globulin) through a vein (intravenously) can lower the risk of coronary artery problems.

- Aspirin. High doses of aspirin may help treat inflammation. Aspirin can also decrease pain and joint inflammation, as well as reduce the fever. Kawasaki treatment is a rare exception to the rule that says aspirin shouldn’t be given to children. Aspirin has been linked to Reye’s syndrome, a rare but potentially life-threatening condition, in children recovering from chickenpox or flu. Children should be given aspirin only under the supervision of a doctor.

Because of the risk of serious complications, initial treatment for Kawasaki disease usually is given in a hospital.

After the initial treatment:

Once the fever goes down, your child may need to take low-dose aspirin for at least six weeks and longer if he or she develops a coronary artery aneurysm. Aspirin helps prevent clotting.

However, if your child develops flu or chickenpox during treatment, he or she may need to stop taking aspirin. Taking aspirin has been linked to Reye’s syndrome, a rare but potentially life-threatening condition that can affect the blood, liver, and brain of children and teenagers after a viral infection.

With treatment, your child may start to improve soon after the first gamma globulin treatment. Without treatment, Kawasaki disease lasts an average of 12 days. However, heart complications may be longer-lasting.

Monitoring heart problems:

If your child has any signs of heart problems, the doctor may recommend follow-up tests to check your child’s heart health at regular intervals, often at six to eight weeks after the illness began, and then again after six months.

If heart problems continue, you may be referred to a doctor who specializes in treating heart disease in children (pediatric cardiologist). Treatment for heart complications related to Kawasaki disease depends on what type of heart condition is present. If a coronary artery aneurysm ruptures, treatment may include anticoagulant drugs, stent placement, or bypass surgery.

Wait to vaccinate

If your child was given gamma globulin, it’s a good idea to wait at least 11 months to get the chickenpox or measles vaccine, because gamma globulin can affect how well these vaccinations work.

History

This disease was first noticed in Japan after the 2nd world war. Two decades later while working at the Tokyo Red Cross Medical Centre in Japan, Tomisaku Kawasaki, noticed in about 50 children from 1961-1967 who presented with a distinctive clinical illness characterized by fever and rash, which was then thought to be a benign childhood illness. There were sudden deaths reported in children less than 2 years of age, who had recovered or were in the process of recovery.

The disease was first reported by Tomisaku Kawasaki in a four-year-old child with a rash and fever at the Red Cross Hospital in Tokyo in January 1961, and he later published a report on 50 similar cases. Later, Kawasaki and colleagues were persuaded of definite cardiac involvement when they studied and reported 23 cases, of which 11 (48%) patients had abnormalities detected by an electrocardiogram. In 1974, the first description of this disorder was published in the English-language literature. In 1976, Melish et al. described the same illness in 16 children in Hawaii. Melish and Kawasaki had independently developed the same diagnostic criteria for the disorder, which are still used today to make the diagnosis of classic Kawasaki disease.

A question was raised about whether the disease only started during the period between 1960 and 1970, but later a preserved heart of a seven-year-old boy who died in 1870 was examined and showed three aneurysms of the coronary arteries with clots, as well as pathologic changes consistent with Kawasaki disease. Kawasaki disease is now recognized worldwide. Why cases began to emerge across all continents around the 1960s and 1970s is unclear. Possible explanations could include confusion with other diseases such as scarlet fever, and easier recognition stemming from modern healthcare factors such as the widespread use of antibiotics. In particular, old pathological descriptions from Western countries of infantile polyarteritis nodosa coincide with reports of fatal cases of Kawasaki disease.

A Blood Pressure Monitor could save a life. Click on the blue for your link. Fast home delivery.

In the United States and other developed nations, Kawasaki disease appears to have replaced acute rheumatic fever as the most common cause of acquired heart disease in children.

In the continental United States, population-based and hospitalization studies estimate an incidence of KD ranging from about 9 to 20 per 100,000 children under 5 years of age. In the year 2016, approximately 5440 hospitalizations with KD were reported among children under 18 years of age in the US; 3935 of these children were under 5 years of age, for a hospitalization rate of 19.8 per 100,000 children in that age group.

Toxic origins:

Kawasaki’s relatively quick onset rules out a viral cause, the researchers say, because the incubation time for most viral infections is several hours longer. “The incubation time suggests we should be looking in a very different direction,” says study co-author Jane Burns, a pediatrics researcher at the University of California, San Diego

Instead, Burns and colleagues suspect a wind-borne toxin made by a plant, fungus, or bacterium. If a wind-borne toxin is indeed responsible, it would be the first disease known to operate in this way, Burns says.

Intriguingly, air samples that the researchers collected from winds blowing from northeastern China to Japan contained an unexpectedly high quantity of the fungus Candida.

“I think there is evidence that [Kawasaki disease] looks like other bacterial toxin diseases,” says Samuel Dominguez, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora.

But David Battisti, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Washington in Seattle, questions whether northeastern China is the region of origin of Kawasaki’s causative agent. He notes that outbreaks of the disease tend to occur in Japan during winter and early spring when cropland in northeastern China is frozen solid, and winds would not stir up many particles.

“It’s an open question still whether the source region in northeast China or maybe even further west,” he says.

The Hunt to Understand COVID-19’s Connection to Kawasaki Disease

Dr. Jane C. Burns has studied Kawasaki disease for four decades. It took only four months for COVID-19 to turn her life’s work upside down.

Unusual numbers of children and teenagers living in COVID-19 hotspots like Lombardy, Italy, and New York City have developed an inflammatory condition (officially called Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children or MIS-C) that looks a lot like Kawasaki disease. In many cases, the children have also tested positive for COVID-19 antibodies, suggesting the syndrome following a viral infection.

In New York State, 170 inflammatory disease cases and three related deaths are under investigation. Ninety-two percent of these patients tested positive for COVID-19 or its antibodies, and almost all of them were younger than 20, according to state health department data. As case reports pile up, the world is suddenly paying attention to the rare pediatric syndrome that has stumped Burns and her colleagues for decades but largely flown under the radar.

“I’ve been waiting 40 years to understand in a much clearer way what I’ve been looking at all my life,” says Burns, who directs the Kawasaki Disease Research Center at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. “It’s a tragedy to realize that this virus that we thought was going to spare our most vulnerable citizens—our children—is not. But it has suddenly presented the opportunity to actually understand Kawasaki disease.”

Kawasaki disease’s connection to COVID-19

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, a few papers had suggested other coronaviruses could cause Kawasaki disease. So when the pandemic hit, Portman expected to see an uptick in Kawasaki-like inflammatory disease, he says.

But some researchers don’t think SARS-CoV-2 has any connection to Kawasaki disease. That’s because MIS-C and Kawasaki have some clear and crucial differences.

Whereas Kawasaki disease is treatable and only leads to significant heart damage in about 25% of cases even when it’s left alone, many MIS-C patients suffer such serious damage to the heart that they go into shock. Others don’t have external symptoms of Kawasaki but do have a high fever and elevated inflammatory markers. Teenagers and young adults have also been showing up in hospitals with MIS-C, whereas Kawasaki almost exclusively strikes children five and younger.

Burns says it’s possible that SARS-CoV-2 affects Kawasaki-prone children differently, depending on their unique genetic blueprints. Some could clear a SARS-CoV-2 infection without any inflammatory response. Others could go on to develop Kawasaki-like illness, while still others might exhibit an inflammatory response slightly different than Kawasaki disease. Burn has applied for a National Institutes of Health grant that would allow her to perform whole-genome sequencing on children with different types of MIS-C, as well as children who were diagnosed with Kawasaki disease before the COVID-19 pandemic, to find differences and similarities.

But Levin isn’t sure there’s enough similarity to consider MIS-C a relative of Kawasaki.

Using data from Burns’ database of pre-COVID-19 Kawasaki patients, Levin compared classic Kawasaki with emerging clinical and laboratory reports of MIS-C. Given the high likelihood that MIS-C results in much more severe symptoms than the typical case of Kawasaki, “the overall spectrum is more different from Kawaski than similar to Kawasaki,” he concludes.

He notes that adults with serious cases of COVID-19 are also seeing extreme inflammatory responses; they just manifest differently, causing issues like respiratory distress. It’s possible that MIS-C is the pediatric version of that inflammation, he says.

Portman says he’s not sure it matters whether MIS-C is a subset of Kawasaki or its own syndrome since they both seem to respond to the same treatment. “My general opinion is that we may have to morph these two diseases into one and just give them subclassifications,” he says.

Both Portman and Levin are working on gathering the data necessary to figure out how best to treat Kawasaki and MIS-C. Levin is launching a database that will allow clinicians to upload anonymous case details and treatment results until more rigorous randomized control trials can be completed, and Portman has been awarded a research grant to study differences in patients who respond to intravenous immunoglobulin versus those who don’t.

Please Always Consult With Your Doctor

Thank you for reading,

Michael

Comments are welcome.

I have never heard about Kawasaki disease before! I didn’t know it was something related to Covid-19. This does not look good and I hope I will never have to fight with this. It really is sad that this virus did not spare the youngest.

In my country there were only 8 death cases of Covid-19, and they were all older and already had some disease. I feel sad for the children in other countries who are gone because of things like this.

Thank you for writing about this issue!

Hi majam97,

Thank you for your comments.

Kawasaki disease has been around for a while. Unfortunately, it is on the rise and has been linked to the outbreak of COVID-19. It is attacking our most innocent and I agree that is sad.

Best wishes,

Michael

so thoughtful of you to share such an important information on this very disease and it’s symptoms and possible treatment….from your review I could tell that kawasaki disease is what no one should on the rate as it’s negligence could lead to severe situation that could go beyond treatment….

thanks for the awesome tips giving on how best to overcome this disease

Hi, evansese,

Thank you for your comments. It seems to be on the rise and we have to look after our children.

Best wishes,

Michael

Hey nice article you have there, your thoughts are indeed invaluable. Kawasaki disease can be divided into three stages: acute, subacute and convalescent. The acute stage usually lasts seven to fourteen days. Most children who have Kawasaki disease usually recover within weeks of getting symptoms and the possibility of having it twice is very rare. Warm Regards

Hi, edahnewton,

Thank you for your comments. Also thank you for sharing your knowledge about Kawasaki disease. Unfortunately not too many people are aware of this.

All the best,

Michael