What is Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia?

Blue indicates link

Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, and eventually the ability to carry out the simplest tasks. In most people with Alzheimer’s, symptoms first appear in their mid-60s.

A bit of history:

Alzheimer’s disease is named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer. In 1906, Dr. Alzheimer noticed changes in the brain tissue of a woman who had died of an unusual mental illness. Her symptoms included memory loss, language problems, and unpredictable behavior. After she died, he examined her brain and found many abnormal clumps (now called amyloid plaques) and tangled bundles of fibers (now called neurofibrillary, or tau, tangles).

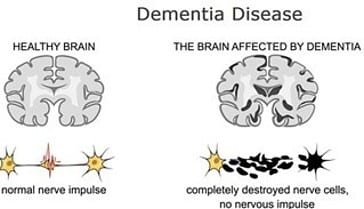

These plaques and tangles in the brain are still considered some of the main features of Alzheimer’s disease. Another feature is the loss of connections between nerve cells (neurons) in the brain. Neurons transmit messages between different parts of the brain, and from the brain to muscles and organs in the body.

According to the Mayo Clinic:

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive disorder that causes brain cells to waste away (degenerate) and die. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia — a continuous decline in thinking, behavioral, and social skills that disrupts a person’s ability to function independently.

The early signs of the disease may be forgetting recent events or conversations. As the disease progresses, a person with Alzheimer’s disease will develop severe memory impairment and lose the ability to carry out everyday tasks.

Current Alzheimer’s disease medications may temporarily improve symptoms or slow the rate of decline. These treatments can sometimes help people with Alzheimer’s disease maximize function and maintain independence for a time. Different programs and services can help support people with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers.

There is no treatment that cures Alzheimer’s disease or alters the disease process in the brain. In the advanced stages of the disease, complications from severe loss of brain function — such as dehydration, malnutrition, or infection — result in death.

In 2013, 6.8 million people in the U.S. had been diagnosed with dementia. Of these, 5 million had a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. By 2050, the numbers are expected to double.

Alzheimer’s disease is currently ranked as the sixth leading cause of death in the United States, but recent estimates indicate that the disorder may rank third, just behind heart disease and cancer, as a cause of death for older people.

Signs and Symptoms

Memory problems are typically one of the first signs of cognitive impairment related to Alzheimer’s disease. Some people with memory problems have a condition called mild cognitive impairment (MCI). In MCI, people have more memory problems than normal for their age, but their symptoms do not interfere with their everyday lives. Movement difficulties and problems with the sense of smell have also been linked to MCI. Older people with MCI are at greater risk for developing Alzheimer’s, but not all of them do. Some may even go back to normal cognition.

The first symptoms of Alzheimer’s vary from person to person. For many, a decline in non-memory aspects of cognition, such as word-finding, vision/spatial issues, and impaired reasoning or judgment, may signal the very early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers are studying biomarkers (biological signs of disease found in brain images, cerebrospinal fluid, and blood) to detect early changes in the brains of people with MCI and in cognitively normal people who may be at greater risk for Alzheimer’s. Studies indicate that such early detection is possible, but more research is needed before these techniques can be used routinely to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease in everyday medical practice.

What Causes Alzheimer’s Disease:

Scientists don’t yet fully understand what causes Alzheimer’s disease in most people. In people with early-onset Alzheimer’s, a genetic mutation may be the cause. Late-onset Alzheimer’s arises from a complex series of brain changes that occur over decades. The causes probably include a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. The importance of any one of these factors in increasing or decreasing the risk of developing Alzheimer’s may differ from person to person.

Scientists believe that for most people, Alzheimer’s disease is caused by a combination of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors that affect the brain over time.

Less than 1 percent of the time, Alzheimer’s is caused by specific genetic changes that virtually guarantee a person will develop the disease. These rare occurrences usually result in disease onset in middle age.

The exact causes of Alzheimer’s disease aren’t fully understood, but at its core are problems with brain proteins that fail to function normally, disrupt the work of brain cells (neurons), and unleash a series of toxic events. Neurons are damaged, lose connections to each other, and eventually die.

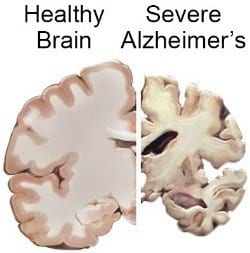

The damage most often starts in the region of the brain that controls memory, but the process begins years before the first symptoms. The loss of neurons spreads in a somewhat predictable pattern to other regions of the brain. By the late stage of the disease, the brain has shrunk significantly.

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive disease.

The first symptoms of Alzheimer’s vary from person to person. For many, a decline in non-memory aspects of cognition, such as word-finding, vision/spatial issues, and impaired reasoning or judgment, may signal the very early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers are studying biomarkers (biological signs of disease found in brain images, cerebrospinal fluid, and blood) to detect early changes in the brains of people with MCI and in cognitively normal people who may be at greater risk for Alzheimer’s. Studies indicate that such early detection is possible, but more research is needed before these techniques can be used routinely to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease in everyday medical practice.

Mild Alzheimer’s Disease:

As Alzheimer’s disease progresses, people experience greater memory loss and other cognitive difficulties. Problems can include wandering and getting lost, trouble handling money and paying bills, repeating questions, taking longer to complete normal daily tasks, and personality and behavior changes. People are often diagnosed in this stage.

Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease:

In this stage, damage occurs in areas of the brain that control language, reasoning, sensory processing, and conscious thought. Memory loss and confusion grow worse, and people begin to have problems recognizing family and friends. They may be unable to learn new things, carry out multi-step tasks such as getting dressed, or cope with new situations. In addition, people at this stage may have hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia and may behave impulsively.

Severe Alzheimer’s Disease:

Ultimately, plaques and tangles spread throughout the brain, and brain tissue shrinks significantly. People with severe Alzheimer’s cannot communicate and are completely dependent on others for their care. Near the end, the person may be in bed most or all of the time as the body shuts down.

Health, Environmental, and Lifestyle Factors:

Research suggests that a host of factors beyond genetics may play a role in the development and course of Alzheimer’s disease. There is a great deal of interest, for example, in the relationship between cognitive decline and vascular conditions such as heart disease, stroke, and high blood pressure, as well as metabolic conditions such as diabetes and obesity. Ongoing research will help us understand whether and how reducing risk factors for these conditions may also reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s.

A nutritious diet, physical activity, social engagement, and mentally stimulating pursuits have all been associated with helping people stay healthy as they age. These factors might also help reduce the risk of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. Clinical trials are testing some of these possibilities.

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease:

To diagnose Alzheimer’s, doctors may:

- Ask the person and a family member or friend questions about overall health, use of prescription and over-the-counter medicines, diet, past medical problems, ability to carry out daily activities, and changes in behavior and personality

- Conduct tests of memory, problem-solving, attention, counting, and language

- Carry out standard medical tests, such as blood and urine tests, to identify other possible causes of the problem

- Perform brain scans, such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or positron emission tomography (PET), to rule out other possible causes for symptoms

These tests may be repeated to give doctors information about how the person’s memory and other cognitive functions are changing over time.

Alzheimer’s disease can be definitely diagnosed only after death, by linking clinical measures with an examination of brain tissue in an autopsy.

People with memory and thinking concerns should talk to their doctor to find out whether their symptoms are due to Alzheimer’s or another cause, such as stroke, tumor, Parkinson’s disease, sleep disturbances, side effects of medication, an infection, or a non-Alzheimer’s dementia. Some of these conditions may be treatable and possibly reversible.

If the diagnosis is Alzheimer’s, beginning treatment early in the disease process may help preserve daily functioning for some time, even though the underlying disease process cannot be stopped or reversed. An early diagnosis also helps families plan for the future. They can take care of financial and legal matters, address potential safety issues, learn about living arrangements, and develop support networks.

In addition, an early diagnosis gives people greater opportunities to participate in clinical trials that are testing possible new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease or other research studies.

Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease:

Alzheimer’s disease is complex, and it is unlikely that any one drug or other intervention can successfully treat it. Current approaches focus on helping people maintain mental function, manage behavioral symptoms, and slow down certain problems, such as memory loss. Researchers hope to develop therapies targeting specific genetic, molecular, and cellular mechanisms so that the actual underlying cause of the disease can be stopped or prevented.

There are some prescription medications that your doctor may advise you to take.

These drugs work by regulating neurotransmitters, the chemicals that transmit messages between neurons. They may help reduce symptoms and help with certain behavioral problems. However, these drugs don’t change the underlying disease process. They are effective for some but not all people and may help only for a limited time.

I know I have mentioned this before, but I feel it necessary to mention it once again:

A nutritious diet, physical activity, social engagement, and mentally stimulating pursuits have all been associated with helping people stay healthy as they age. These factors might also help reduce the risk of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. Clinical trials are testing some of these possibilities.

It seems This article would not be complete without the mention of dementia.

Data show that more than 419,000 Canadians (65 years and older) are living with diagnosed dementia, almost two-thirds of whom are women. As this number does not include those under age 65 who may have a young-onset diagnosis or those who have not been diagnosed, the true picture of dementia in Canada may be somewhat larger. With a growing and aging population, the number of Canadians with dementia is expected to increase.

What is dementia?

Dementia is an overall term for a set of symptoms that are caused by disorders affecting the brain. Symptoms may include memory loss and difficulties with thinking, problem-solving, or language, severe enough to reduce a person’s ability to perform everyday activities. A person with dementia may also experience changes in mood or behavior.

Dementia is progressive, which means the symptoms will gradually get worse as more brain cells become damaged and eventually die.

Dementia is not a specific disease. Many diseases can cause dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia (due to strokes), Lewy Body disease, head trauma, frontotemporal dementia, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease. These conditions can have similar and overlapping symptoms.

Some treatable conditions can produce symptoms similar to dementia, for example, vitamin deficiencies, thyroid disease, sleep disorders, or mental illness. It is therefore important to arrange for a full medical assessment as early as possible.

Getting a timely diagnosis can help you access information, resources, and support through the Alzheimer Society, benefit from treatment, and plan ahead.

What Causes Dementia?

The most common causes of dementia include:

- Degenerative neurological diseases. These include Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and some types of multiple sclerosis. These diseases get worse over time.

- Vascular disorders. These are disorders that affect the blood circulation in your brain.

- Traumatic brain injuries caused by car accidents falls, concussions, etc.

- Infections of the central nervous system. These include meningitis, HIV, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

- Long-time alcohol or drug use

- Certain types of hydrocephalus, a buildup of fluid in the brain

More Causes:

Dementia is caused by damage to or loss of nerve cells and their connections in the brain. Depending on the area of the brain that’s affected by the damage, dementia can affect people differently and cause different symptoms.

Dementias are often grouped by what they have in common, such as the protein or proteins deposited in the brain or the part of the brain that’s affected. Some diseases look like dementias, such as those caused by a reaction to medications or vitamin deficiencies, and they might improve with treatment.

Dementia-like conditions that can be reversed:

Some causes of dementia or dementia-like symptoms can be reversed with treatment. They include:

- Infections and immune disorders. Dementia-like symptoms can result from fever or other side effects of your body’s attempt to fight off an infection. Multiple sclerosis and other conditions caused by the body’s immune system attacking nerve cells also can cause dementia.

- Metabolic problems and endocrine abnormalities. People with thyroid problems, low blood sugar (hypoglycemia), too little or too much sodium or calcium, or problems absorbing vitamin B-12 can develop dementia-like symptoms or other personality changes.

- Nutritional deficiencies. Not drinking enough liquids (dehydration); not getting enough thiamine (vitamin B-1), which is common in people with chronic alcoholism; and not getting enough vitamins B-6 and B-12 in your diet can cause dementia-like symptoms. Copper and vitamin E deficiencies also can cause dementia symptoms.

- Medication side effects. Side effects of medications, a reaction to a medication, or an interaction of several medications can cause dementia-like symptoms.

- Subdural hematomas. Bleeding between the surface of the brain and the covering over the brain, which is common in the elderly after a fall, can cause symptoms similar to those of dementia.

- Poisoning. Exposure to heavy metals, such as lead, and other poisons, such as pesticides, as well as recreational drug or heavy alcohol use, can lead to symptoms of dementia. Symptoms might resolve with treatment.

- Brain tumors. Rarely, dementia can result from damage caused by a brain tumor.

- Anoxia. This condition, also called hypoxia, occurs when organ tissues aren’t getting enough oxygen. Anoxia can occur due to severe sleep apnea, asthma, heart attack, carbon monoxide poisoning, or other causes.

- Normal-pressure hydrocephalus. This condition, which is caused by enlarged ventricles in the brain, can cause walking problems, urinary difficulty, and memory loss.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosing dementia and its type can be challenging. People have dementia when they have cognitive impairment and lose their ability to perform daily functions, such as taking their medication, paying bills, and driving safely.

To diagnose the cause of dementia, the doctor must recognize the pattern of the loss of skills and function and determine what a person is still able to do. More recently, biomarkers have become available to make a more accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease.

Your doctor will review your medical history and symptoms and conduct a physical examination. He or she will likely ask someone close to you about your symptoms as well.

No single test can diagnose dementia, so doctors are likely to run a number of tests that can help pinpoint the problem.

Lewy Body Dementia:

Many Americans first heard about Lewy Body Dementia (LBD) after it was revealed that comedy legend Robin Williams suffered from the disease at the time of his death. Considered by some experts to be the second most common form of dementia, LBD affects an estimated 1.4 million Americans. In this type of dementia, Lewy bodies–or abnormal deposits of a protein known as alpha-synuclein–are present in the brain, impeding normal cognitive function.

Many people with LBD are initially misdiagnosed, because they may experience symptoms that are common in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. People with LBD experience reduced attention and alertness, which may mimic the memory problems of someone with Alzheimer’s. However, memory is fairly intact in people with LBD, although their problem-solving skills tend to be highly impaired.

Hallucinations are also common in the early stage of the disorder (unlike in Alzheimer’s, where this symptom occurs in the later stages). Like people with Parkinson’s disease, those with Lewy body dementia may have mobility problems–slow, stiff, or shaky movements, trouble balancing, and a shuffling walk.

It’s also common for people with LBD to have one or more sleep disorders, including REM sleep disorder behavior (RBD), in which they physically act out their dreams. RBD, which can begin years or even decades before Lewy body dementia appears, can cause injuries to those living with the condition and to their sleeping partner.

Vascular Dementia:

The Alzheimer’s Association considers vascular dementia to be the second most common form of dementia. (Statistics vary widely, but it’s estimated that it affects one to four percent of people over 65.) This disorder, which often begins abruptly, is caused by poor blood flow to the brain, resulting from any number of conditions that narrow the blood vessels, including stroke, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

Usually, the culprit is multiple small strokes (infarcts) caused by blood clots or thickened or ruptured small arteries that connect to the center of the brain. (This is called multi-infarct dementia.) The type of dementia may also be caused by one big stroke (which would be referred to as post-stroke dementia).

Symptoms of vascular dementia include confusion, disorientation, and trouble following directions. Recall of day-to-day events (episodic memory) becomes impaired, but recognition–of people, for example–doesn’t. Vascular dementia loss may progress to hallucinations, agitation, or withdrawal, and symptoms may clearly worsen after each successive stroke.

Frontotemporal Dementia:

FTD, which usually occurs between ages 40 to 45, affects personality significantly, usually resulting in a decline in empathy, as well as social skills. People with this disorder may exhibit increasingly inappropriate actions and repetitive compulsive behavior, including the consumption of inedible objects. Frontotemporal dementia is also associated with impaired judgment, mood swings, and apathy. Some subtypes of FTD are marked by a decline in speech while even rarer subtypes feature mobility problems like those seen in Parkinson’s.

Did you know that nearly six out of 10 older Americans with dementia are undiagnosed or unaware of their diagnosis, and many others are misdiagnosed? It can be a mistake to assume that cognitive issues are caused by Alzheimer’s. If the decline is caused by another condition, treatments used for Alzheimer’s might be ineffective or even harmful.

People with Lewy body dementia, for example, are often highly sensitive to the antipsychotics sometimes used to treat behavioral symptoms in people with Alzheimer’s. Also, keep in mind that dementia-like symptoms are sometimes caused by conditions like nutritional deficiencies and infections that can be reversed if the underlying cause is treated. (Alzheimer’s disease and many other dementias including LBD are incurable.)

Early and accurate diagnosis of dementia is critical to effectively managing it. If your loved one’s doctor is not familiar with the complexities of a dementia diagnosis, ask for a referral to a neurologist, especially one specializing in dementia, who will test your loved one’s memory, thinking abilities, and movement. Also consider a referral to a geriatrician, a doctor with specialized training in treating older adults.

Diagnosing dementia requires a physical exam and blood tests, plus a full review of the patient’s health care, family history, and medication history. Doctors will talk to you and other family members about symptoms and behaviors you have witnessed and will evaluate your loved one for a host of conditions, including:

- Depression

- Substance abuse

- Anemia

- Vitamin deficiencies

- Diabetes

- Kidney or liver disease

- Thyroid disease

- Infections

- Cardiovascular and pulmonary problems

Mixed dementia:

Autopsy studies of the brains of people 80 and older who had dementia indicate that many had a combination of several causes, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and Lewy body dementia. Studies are ongoing to determine how having mixed dementia affects symptoms and treatments.

Prevention:

There’s no sure way to prevent dementia, but there are steps you can take that might help. More research is needed, but it might be beneficial to do the following:

- Keep your mind active. Mentally stimulating activities, such as reading, solving puzzles playing word games, and memory training might delay the onset of dementia and decrease its effects.

- Be physically and socially active. Physical activity and social interaction might delay the onset of dementia and reduce its symptoms. Move more and aim for 150 minutes of exercise a week.

- Quit smoking. Some studies have shown that smoking in middle age and beyond may increase your risk of dementia and blood vessel (vascular) conditions. Quitting smoking might reduce your risk and will improve your health.

- Get enough vitamins. Some research suggests that people with low levels of vitamin D in their blood are more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. You can get vitamin D through certain foods, supplements, and sun exposure. More study is needed before an increase in vitamin D intake is recommended for preventing dementia, but it’s a good idea to make sure you get adequate vitamin D. Taking a daily B-complex vitamin and vitamin C may also be helpful.

- Manage cardiovascular risk factors. Treat high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, and high body mass index (BMI). High blood pressure might lead to a higher risk of some types of dementia. More research is needed to determine whether treating high blood pressure may reduce the risk of dementia.

- Treat health conditions. See your doctor for treatment if you experience hearing loss, depression, or anxiety.

- Maintain a healthy diet. Eating a healthy diet is important for many reasons, but a diet such as the Mediterranean diet — rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and omega-3 fatty acids, which are commonly found in certain fish and nuts — might promote health and lower your risk of developing dementia. This type of diet also improves cardiovascular health, which may help lower dementia risk. Try eating fatty fish such as salmon three times a week, and a handful of nuts — especially almonds and walnuts — daily.

- Get quality sleep. Practice good sleep hygiene, and talk to your doctor if you snore loudly or have periods where you stop breathing or gasp during sleep.

In most cases where the disease occurs, if not genetic: Your diet (nutrition), exercise, both physical and mental, sunshine, and proper sleep. These are all things you can control. Smoking and excessive drinking are things to keep in mind to maintain a healthy lifestyle.

Thank you for reading,

Michael.

Comments are welcome.

This post is a very educative one full of many things that one can really learn from. I like the way you have written this here. The Alzheimer’s disease is one that looks to be very serious especially if not taken seriously. I have a friend who is showing some of these symptoms but his family thinks that it might be a case of dementia. I think he really needs to see a doctor. This has opened my eyes. Thank you!

Hi Henderson,

Thank you for your comments. Dementia is considered what is called an umbrella to Alzheimer’s disease. There are associative test’s that can be done by a Doctor that can determine dementia.

https://www.cbc.ca/natureofthi…

https://www.pinterest.ca/pin/5…

Some of Dr. Suziki’s findings on Alzheimer’s that I found informative.

Best wishes,

Michael

WOw, looks like something really serious and I can understand from here how dementia is related to the Alzheimer’s disease. This is a very nice post and i was well educated about it and how it really affects the brain. Do you think that one can be said to have Alzheimer’s disease for just having memory loss alone? Because it seems like that it an underlying symptom.

Hi John,

Thank you for your comments. Memory loss happens to a lot of people including myself. There are no definite links between Alzheimer’s. There are certain associative tests that can be done to determine any signs of dementia.

Recently I saw a documentary by Dr. Suziki, that sheds more light on the disease.

https://www.pinterest.ca/pin/548172585866967622/

https://www.cbc.ca/natureofthi…

Best wishes,

Michael

Hello Michael,

After reading your very informative article about Alzheimer’s, it frightens me to suffer it in the future.

I find it incredible how many people in the world suffer from this brain disease.

I like knowing what you say how can we prevent it? With healthy nutrition, performing a physical activity and with a social commitment.

I personally believe to be in line with these 3 tips, I am 61 years old. I hope to live well the rest of my life for me and for the rest of my family.

Thank you!

Hi Claudio,

Thank you for your feed back. You will live well and healthy.

I recently saw a documentary by Dr. Suziki, where scientists have found a link to a lack of insulin in the brain that may be linked to this sad unfortunate disease.

https://www.pinterest.ca/pin/548172585866967622/

https://www.pinterest.ca/pin/548172585866967622/

Best wishes,

Michael