What Is HPV?

Blue indicates link

Human Papillomavirus:

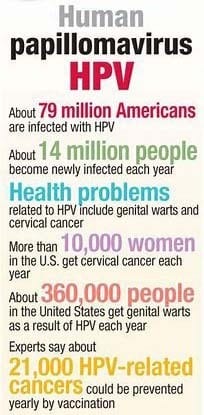

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI). HPV is a different virus than HIV and HSV (herpes). 79 million Americans, most in their late teens and early 20s, are infected with HPV. There are many different types of HPV. Some types can cause health problems including genital warts and cancers. But there are vaccines that can stop these health problems from happening.

Most cervical cancers are associated with human papillomavirus (HPV), a sexually transmitted infection. Widespread immunization with the HPV vaccine could reduce the impact of cervical cancer worldwide. Here’s what you need to know about the HPV vaccine.

How is HPV spread?

You can get HPV by having vaginal, anal, or oral sex with someone who has the virus. It is most commonly spread during vaginal or anal sex. HPV can be passed even when an infected person has no signs or symptoms.

Anyone who is sexually active can get HPV, even if they have had sex with only one person. You also can develop symptoms years after you have sex with someone who is infected. This makes it hard to know when you first became infected.

Does HPV cause health problems?

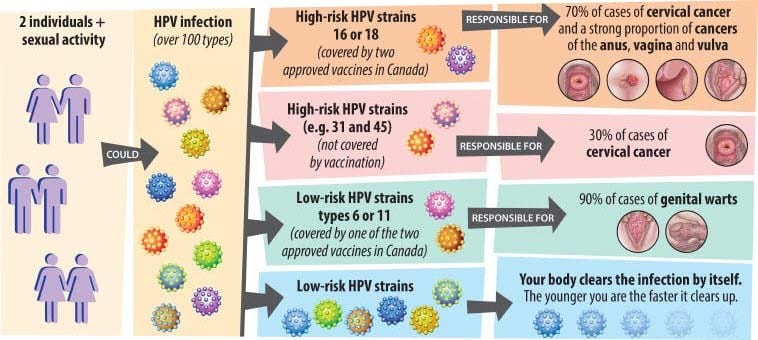

In most cases, HPV goes away on its own and does not cause any health problems. But when HPV does not go away, it can cause health problems like genital warts and cancer.

Genital warts usually appear as a small bump or group of bumps in the genital area. They can be small or large, raised or flat, or shaped like a cauliflower. A healthcare provider can usually diagnose warts by looking at the genital area.

Does HPV cause cancer?

HPV can cause cervical and other cancers including cancer of the vulva, vagina, penis, or anus. It can also cause cancer in the back of the throat, including the base of the tongue and tonsils (called oropharyngeal cancer).

Cancer often takes years, even decades, to develop after a person gets HPV. The types of HPV that can cause genital warts are not the same as the types of HPV that can cause cancers.

There is no way to know which people who have HPV will develop cancer or other health problems. People with weak immune systems (including those with HIV/AIDS) may be less able to fight off HPV. They may also be more likely to develop health problems from HPV.

How can I avoid HPV and the health problems it can cause?

You can do several things to lower your chances of getting HPV.

Get vaccinated. The HPV vaccine is safe and effective. It can protect against diseases (including cancers) caused by HPV when given in the recommended age groups. (See “Who should get vaccinated?” below) CDC recommends HPV vaccination at age 11 or 12 years (or can start at age 9 years) and for everyone through age 26 years, if not vaccinated already. For more information on the recommendations, please see: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/public/index.html

Get screened for cervical cancer. Routine screening for women aged 21 to 65 years old can prevent cervical cancer.

If you are sexually active

- Use latex condoms the right way every time you have sex. This can lower your chances of getting HPV. But HPV can infect areas not covered by a condom – so condoms may not fully protect against getting HPV;

- Be in a mutually monogamous relationship – or have sex only with someone who only has sex with you.

How do I know if I have HPV?

There is no test to find out a person’s “HPV status.” Also, there is no approved HPV test to find HPV in the mouth or throat.

There are HPV tests that can be used to screen for cervical cancer. These tests are only recommended for screening in women aged 30 years and older. HPV tests are not recommended to screen men, adolescents, or women under the age of 30 years.

Most people with HPV do not know they are infected and never develop symptoms or health problems from it. Some people find out they have HPV when they get genital warts. Women may find out they have HPV when they get an abnormal Pap test result (during cervical cancer screening). Others may only find out once they’ve developed more serious problems from HPV, such as cancers.

How common are HPV and the health problems caused by HPV?

HPV (the virus): About 79 million Americans are currently infected with HPV. About 14 million people become newly infected each year. HPV is so common that almost every person who is sexually active will get HPV at some time in their life if they don’t get the HPV vaccine.

Health problems related to HPV include genital warts and cervical cancer.

Genital warts: Before HPV vaccines were introduced, roughly 340,000 to 360,000 women and men were affected by genital warts caused by HPV every year.* Also, about one in 100 sexually active adults in the U.S. has genital warts at any given time.

Cervical cancer: Every year, nearly 12,000 women living in the U.S. will be diagnosed with cervical cancer, and more than 4,000 women die from cervical cancer—even with screening and treatment.

There are other conditions and cancers caused by HPV that occur in people living in the United States. Every year, approximately 19,400 women and 12,100 men are affected by cancers caused by HPV.

I’m pregnant. Does having HPV affect my pregnancy?

If you are pregnant and have HPV, you can get genital warts or develop abnormal cell changes on your cervix. Abnormal cell changes can be found with routine cervical cancer screening. You should get routine cervical cancer screening even when you are pregnant.

Can I be treated for HPV or health problems caused by HPV?

There is no treatment for the virus itself. However, there are treatments for the health problems that HPV can cause:

- Genital warts can be treated by your healthcare provider or with prescription medication. If left untreated, genital warts may go away, stay the same, or grow in size or number.

- Cervical precancer can be treated. Women who get routine Pap tests and follow-up as needed can identify problems before cancer develops. Prevention is always better than treatment. For more information visit www.cancer.orgexternal icon.

- Other HPV-related cancers are also more treatable when diagnosed and treated early. For more information visit www.cancer.orgexternal icon

Who should get vaccinated?

HPV vaccination is recommended at age 11 or 12 years (or can start at age 9 years) and for everyone through age 26 years, if not vaccinated already.

Vaccination is not recommended for everyone older than age 26 years. However, some adults aged 27 through 45 years who are not already vaccinated may decide to get the HPV vaccine after speaking with their healthcare provider about their risk for new HPV infections and the possible benefits of vaccination. HPV vaccination in this age range provides less benefit. Most sexually active adults have already been exposed to HPV, although not necessarily all of the HPV types targeted by vaccination.

At any age, having a new sex partner is a risk factor for getting a new HPV infection. People who are already in a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship are not likely to get a new HPV infection.

What does the HPV vaccine do?

Various strains of HPV spread through sexual contact and are associated with most cases of cervical cancer. Gardasil 9 is an HPV vaccine approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and can be used for both girls and boys.

This vaccine can prevent most cases of cervical cancer if given before a girl or woman is exposed to the virus. In addition, this vaccine can prevent vaginal and vulvar cancer in women and can prevent genital warts and anal cancer in women and men.

In theory, vaccinating boys against the types of HPV associated with cervical cancer might also help protect girls from the virus by possibly decreasing transmission. Certain types of HPV have also been linked to cancers in the mouth and throat, so the HPV vaccine likely offers some protection against these cancers, too.

Who is the HPV vaccine for and when should it be given?

The HPV vaccine is routinely recommended for girls and boys ages 11 or 12, although it can be given as early as age 9. It’s ideal for girls and boys to receive the vaccine before they have sexual contact and are exposed to HPV. Research has shown that receiving the vaccine at a young age isn’t linked to an earlier start of sexual activity.

Once someone is infected with HPV, the vaccine might not be as effective or might not work at all. Also, the response to the vaccine is better at younger ages than it is at older ages.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommends that all 11- and 12-year-olds receive two doses of HPV vaccine at least six months apart, instead of the previously recommended three-dose schedule. Younger adolescents aged 9 and 10 and teens ages 13 and 14 also are able to receive a vaccination on the updated two-dose schedule. Research has shown that the two-dose schedule is effective for children under 15.

Teens and young adults who begin the vaccine series later, at ages 15 through 26, should continue to receive three doses of the vaccine.

The CDC now recommends catch-up HPV vaccinations for all people through age 26 who aren’t adequately vaccinated.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently approved the use of Gardasil 9 for males and females ages 9 to 45.

Who should not get the HPV vaccine?

The HPV vaccine isn’t recommended for pregnant women or people who are moderately or severely ill. Tell your doctor if you have any severe allergies, including an allergy to yeast or latex. Also, if you’ve had a life-threatening allergic reaction to any component of the vaccine or to a previous dose of the vaccine, you shouldn’t get the vaccine.

Does the HPV vaccine offer benefits if you’re already sexually active?

Yes. Even if you already have one strain of HPV, you could still benefit from the vaccine because it can protect you from other strains that you don’t yet have. However, none of the vaccines can treat an existing HPV infection. The vaccines protect you only from specific strains of HPV you haven’t been exposed to already.

Does the HPV vaccine carry any health risks or side effects?

Overall, the effects are usually mild. The most common side effects of HPV vaccines include soreness, swelling, or redness at the injection site.

Sometimes dizziness or fainting occurs after the injection. Remaining seated for 15 minutes after the injection can reduce the risk of fainting. In addition, headaches, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, or weakness also may occur.

The CDC and the FDA continue to monitor the vaccines for unusual or severe problems.

Is the HPV vaccine required for school enrollment?

The HPV vaccine is part of the routine childhood vaccine schedule. Whether a vaccine becomes a school enrollment requirement is decided on a state-by-state basis.

Do women who’ve received the HPV vaccine still need to have Pap tests?

Yes. The HPV vaccine isn’t intended to replace Pap tests. Routine screening for cervical cancer through regular Pap tests beginning at age 21 remains an essential part of a woman’s preventive health care.

What can you do to protect yourself from cervical cancer if you’re not in the recommended vaccine age group?

HPV spreads through sexual contact — oral, vaginal, or anal. To protect yourself from HPV, use a condom every time you have sex. In addition, don’t smoke. Smoking raises the risk of cervical cancer.

To detect cervical cancer in the earliest stages, see your healthcare provider for regular Pap tests beginning at age 21. Seek prompt medical attention if you notice any signs or symptoms of cervical cancer — vaginal bleeding after sex, between periods or after menopause, pelvic pain, or pain during sex.

HPV Vaccination Controversies

Type/name given to vaccine: Gardasil 9

Gardasil 9 vaccine side effects

Get emergency medical help if you have signs of an allergic reaction to Gardasil 9: hives; difficulty breathing; swelling of your face, lips, tongue, or throat.

Keep track of any and all side effects you have after receiving this vaccine. When you receive a booster dose, you will need to tell the doctor if the previous shot caused any side effects.

You may feel faint after receiving this vaccine. Some people have had seizure-like reactions after receiving this vaccine. Your doctor may want you to remain under observation during the first 15 minutes after the injection.

Developing cancer from HPV is much more dangerous to your health than receiving the vaccine to protect against it. However, like any medicine, this vaccine can cause side effects but the risk of serious side effects is extremely low.

Common Gardasil 9 side effects may include:

- pain, swelling, itching, bruising, bleeding, redness, or a hard lump where the shot was given;

- headache;

- nausea;

- fever; or

- dizziness.

This is not a complete list of side effects and others may occur. Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You may report vaccine side effects to the US Department of Health and Human Services at 1-800-822-7967.

It has been confirmed that 11 deaths after HPV vaccination have been reported to Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). They include one neonatal death in 2008, the death in June this year of an 11-year-old boy who had brain cancer, two deaths that are directly stated to be from cervical cancer, and two in which the adverse reaction is simply described as “vaccination failure”.

The new FOI release also includes four cases of spontaneous abortion after HPV vaccination.

The latest information has come to light via a second Freedom of Information (FOI) request submitted to the TGA by Michelle Stubbs, whose daughter Asha became seriously ill after the HPV vaccination.

The response to Stubbs’ first FOI request revealed that more than one hundred cases of reported adverse reactions after HPV vaccination have been excluded from the TGA’s public Database of Adverse Event Notifications (DAEN). and are only recorded in its Adverse Event Management System (AEMS) internal database.

Stubbs, who lives in northern Queensland, is organizing a class-action lawsuit against Merck, which manufactures Gardasil and Gardasil 9. A total of 150 potential claimants have come forward in less than two months.

For the past couple of years, Stubbs has been doggedly chasing up information, putting questions to the TGA and the Department of Health about her daughter’s case and HPV vaccination in general.

Gardasil is promoted as an “anti-cancer” vaccine and pro-Gardasil lobbyists claim, without foundation, that it will lead to the elimination of cervical cancer in Australia.

Official statistics show the opposite and indicate that, in Australia, Britain, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and the Netherlands, the incidence of cervical cancer has increased among young women since HPV vaccination began. It has never been proved that HPV vaccination has, or ever will, prevented a single case of cancer.

The information just released to Stubbs indicates that two of the reported deaths after HPV vaccination occurred within a period of four days in 2018 (in both cases the adverse effect is listed as vaccination failure). Three of the deaths that year occurred over a period of three weeks. In all three cases, vaccination failure is specified. Cervical cancer is specifically cited as an adverse reaction in only one of those cases. The patient’s age, in that case, is not given.

In the case of one of the deaths listed in the new FOI disclosure, the 23-year-old woman had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a condition in which a portion of the heart becomes thickened. This results in the heart being less able to pump blood effectively. In another, a 13-year-old girl died after suffering from a progression of motor neuron disease.

August 19, 2009 — — A government report released Tuesday raises new questions about the safety of the cervical cancer vaccine Gardasil. The vaccine has been linked to 32 unconfirmed deaths and shows higher incidences of fainting and blood clots than other vaccines.

But while some physicians expressed concern over the findings, other doctors viewed the report as reassuring, showing that the vaccine was not associated with any more unusual and serious side effects than other vaccines.

The results of the report appeared along with an accompanying editorial discussing whether the potential benefit of the HPV vaccine is worth its potential risks in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The editorial, in particular, could give pause to many parents faced with the decision of whether or not to have their 11- and 12-year-old daughters vaccinated against certain strains of the human papillomavirus, or HPV.

On Wednesday morning, ABC News Chief Medical Editor Dr. Timothy Johnson said that he, too, would encourage parents to learn more about the shot before getting their daughters vaccinated.

“I am very much in favor of childhood vaccines,” Johnson told Chris Cuomo on Wednesday’s “Good Morning America,” adding that there is little doubt that the vaccine does have its benefits.

“We know it does what it says – it prevents HPV infections,” he said.

But he added that when it comes to comparing the benefits of the HPV vaccine against its potential risks, he believes there simply is not enough evidence to recommend to all parents that they have their daughters vaccinated.

“I don’t think we yet know the long-term benefits or risks,” Johnson said. “I’m taking a pass on this one and saying to parents, ‘Study the issue, read the editorial… talk to your doctor.'”

Those who search for more information on the vaccine may also find stories from other parents who say the vaccine had ill effects on their daughters. One of these parents, Emily Tarsell, started her daughter Christina on Gardasil — a vaccine that protects against four of the most common cancer-causing strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV) — after her first visit to a gynecologist and at the doctor’s recommendation.

Eighteen days after Christina received her final vaccine shot, she died.

“I know it was the Gardasil,” Tarsell said, although the official cause of death was undetermined. “They were really recommending it, saying that there weren’t any side effects, that it was safe. So I kind of went against my better instinct [and let her] get the shot.”

Deaths like Christina’s are one of several types of complications reported to the U.S. Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) following Gardasil distribution in 2006. Some of these adverse events were serious, including blood clots and neurological disorders, and some were non-life-threatening side effects from the vaccine, including fainting, nausea, and fever.

Although experts agree that the accuracy of data from VAERS reports — which can be made by anyone and are not verified or controlled for quality — is questionable, they remain divided as to whether extreme adverse events, which are serious but rare, are cause enough to stop recommending and administering the Gardasil vaccine without further investigation.

Report Shows Rare But Serious Side Effects May Result From Gardasil Vaccine

“Although the number of serious adverse events is small and rare, they are real and cannot be overlooked or dismissed without disclosing the possibility to all other possible vaccine recipients,” said Dr. Diane Harper, director of the Gynecologic Cancer Prevention Research Group at the University of Missouri. “The rate of serious adverse events is greater than the incidence rate of cervical cancer.”

As of June 1, 2009, the CDC reported that over 25 million doses of Gardasil, which is recommended for women between ages 9-26, have been distributed in the U.S. and there was an average of 53.9 VAERS reports per 100,000 vaccine doses. Of these, 40 percent occurred on the day of vaccination, and 6.2 percent were serious, including 32 reports of death.

In a statement yesterday from Merck, the pharmaceutical company that manufactures Gardasil, the company backed the vaccine’s efficacy and said they encourage further research on its safety.

“We are pleased that the study published by JAMA further reinforces the safety profile of Gardasil,” said Dr. Richard M. Haupt, head of the clinical program for Gardasil at Merck. “We welcome continued study and discussion about the safety of this important vaccine.”

However, some clinicians are not ready to accept wide use of the drug based on the available safety data.

Dr. Jacques Moritz, director of gynecology at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital, said he would not offer the Gardasil vaccine to patients when good cervical cancer screening techniques and treatments exist. He has also chosen not to have his 11-year-old daughter get the HPV shot because of his concerns.

“I’m pro-preventing cervical cancer and HPV,” Moritz said. “I’m not pro that the physicians don’t know the risks and side effects.”

VAERS Report Is No Measuring Stick For Gardasil Side Effects

However, clinicians on both sides of the vaccination debate agree that data provided by the VAERS report is limited because it lacks any baseline comparison for the adverse events reported. This makes it difficult to draw cause-and-effect relationships when a death, for example, occurs soon after administering the Gardasil vaccine.

In fact, the JAMA study authors showed that 90 percent of those with blood clots had typical risk factors for clots, outside of having received the vaccine — using oral contraceptives, for example, or smoking.

“The problem is that there is a difference between an adverse reaction caused by the vaccine, as opposed to an adverse event reported in association with the vaccine,” said Dr. Lauren Streicher, an obstetrician-gynecologist at Northwestern Medical School, who supports the use of the vaccine. “Patients need to understand the true risk of the vaccine, as well as the risks of not getting the vaccine.”

Understanding Risks and Side Effects Essential For Recommending Gardasil

The overwhelming consensus regarding Gardasil’s use is that physicians who are not well versed in the risks of HPV and cervical cancer and the side effects of the vaccine cannot adequately counsel patients on whether or not to be vaccinated.

Dr. Joseph Zanga, chief of pediatrics at the Columbus Regional Healthcare System in Columbus, Ga., pointed out that Gardasil does not prevent women from contracting HPV in every instance, that many people who are infected will spontaneously rid themselves of the virus, and that routine pap smears are still the best prevention against cervical cancer.

“Perhaps the most important, currently missing ‘warning’ is that the vaccine may not be forever,” Zanga said. “We know that it protects for 5-7 years so that a girl getting the series at [age] 11-12 will enter the time of her most likely sexual debut unprotected but believing herself to be.”

Personal Note:

Almost with everything, there are two sides to a story. Your best defense is to be well-informed. Ask lots of questions. This is a matter of life and death.

Thank you for reading

Michael

Comments are welcome

Hello there!

That is a very wonderful article you have there and it is very helpful to the health of people. I am just hearing about HPV and HPV Vaccination and i believe there are many people who have not heard this before too. It is very great to come accross this article and know about HPV and the effects it can have on a person’s health system. This article has also provided aid on how to manage or prevent it. That was really jealpful.

Thanks.

Hi Kingsking,

Thank you for your comments.

The more people that are aware, the more people can be protected and live safe healthy lives.

Best Wishes,

Michael